How to Buy a House in Japan as a Foreigner in 2025 (Step-by-Step Guide)

Introduction: Why Foreigners Are Eyeing Cheap Houses in Japan

Japan’s real estate landscape is unlike any other. New figures show nearly 14% of all houses in Japan are empty – about 9 million homes – due to decades of population decline and urban migration. This glut of akiya (abandoned homes) has created a unique buyer’s market, with incredibly cheap houses in Japan attracting growing interest from overseas buyers. Many people dream of a tranquil countryside home or a rustic fixer-upper in Japan – like this listing in Tottori currently available for $7,000:

Several factors fuel this trend. For one, Japan real estate is very open to foreign buyers. There are no legal restrictions on foreigners buying property in Japan, which means you can even own land outright – a rarity in many other Asian countries. Additionally, a recent surge in foreign interest has been spurred by a weaker yen and Japan’s open-door policy. In fact, the favorable exchange rate and welcoming market have led to a surge in foreign real estate purchases in Japan in recent years. The allure is obvious: there are even cases of cheap houses in Japan under $10,000, or local governments literally giving away homes for free to revitalize rural areas.

Buying a house in Japan as a foreigner in 2025 is very feasible, but it helps to understand the process and pitfalls. Below, we’ll cover everything from legal considerations and the step-by-step buying process to where to find listings for cheap houses (akiya), hidden costs and renovation tips, the pros and cons of akiyas, and real-life examples. By the end, you’ll have a clear roadmap for owning a piece of Japan’s property market – even if you’re not a Japanese citizen.

Legal Restrictions and What Foreigners Need to Know

One of the first questions is usually: Can foreigners buy property in Japan? The answer is yes – absolutely. Japan imposes no special restrictions on foreign buyers. Foreigners have the same property ownership rights as Japanese citizens, meaning you can purchase both land and buildings with full freehold ownership. There are no citizenship or residency requirements to buy real estate in Japan. Unlike some countries, you don’t need to be married to a local or hold a specific visa. In fact, you can purchase property even if you’re on a tourist visa or living abroad.

(Do note, however, that owning property does not grant you residency – buying a house won’t automatically provide a visa or permit to live in Japan long-term.)

From a legal standpoint, foreigners buying property in Japan are treated the same as locals in terms of ownership rules and taxes. Property ownership is permanent (no leasehold limits) and can be bought, sold, or inherited freely. Foreign owners pay the same taxes as Japanese owners when acquiring real estate. This includes one-time acquisition taxes and recurring property taxes (more on those later). There are no extra foreigner surcharges on property, unlike some other nations.

A few things foreigners should keep in mind:

- Visa status: You don’t need any particular visa to buy a house, but you’ll obviously need a valid visa to live in it for extended periods. Owning a home won’t give you a visa, so plan your residency status accordingly (e.g. long-term work visa, spouse visa, etc., if you intend to reside year-round). It’s perfectly legal to own a vacation home on just a tourist entry, but you’d be limited to staying 90 days at a time unless you secure another visa.

- Financing: Getting a Japanese mortgage as a non-resident can be challenging. Japanese banks typically require you to be a resident with a work history in Japan, a local income, and often a permanent residency or a Japanese guarantor. If you don’t meet those, you may need to pay cash or seek financing from your home country. Some international banks and specialty lenders do offer loans for foreign investors, but expect stricter terms. If you are a resident foreigner with a stable income in Japan, some banks will lend – usually requiring a hefty down payment and thorough documentation.

- Taxes and fees: As an owner, you’ll be on the hook for all standard taxes. When you buy, you’ll pay a property acquisition tax, stamp duty, and registration fees, among others. Each year, you’ll owe fixed asset tax (and city planning tax if applicable) just like locals. If you’re not residing in Japan, you may need to appoint a local tax agent to handle property tax bills on your behalf. The good news is Japan’s property taxes are relatively modest – fixed asset tax is about 1.4% of the assessed value annually. Just be sure to budget for these obligations to avoid surprises.

- Ownership regulations: In general there are none specific to foreigners. One minor caveat is a 2021 law that allows the government to review foreign land purchases near sensitive areas (like military bases or border islands). This is unlikely to affect someone buying a home in a normal neighborhood or rural town. Essentially, for typical residential property, foreigners face no special legal hurdles.

- Inheritance: Foreigners can inherit and bequeath property in Japan freely. If you plan to pass the home to family, Japanese inheritance tax laws would apply (which can be complex if neither party is a resident, but that’s beyond this scope). The key point is there’s no law forcing a sale if a foreigner inherits a property – it can stay in the family.

In short, Japan is very welcoming to foreign property buyers. You have full ownership rights, but also the same responsibilities (taxes, maintenance, etc.) as any homeowner. Next, we’ll walk through how to buy a house in Japan step by step, especially tailored for those who may not speak Japanese fluently.

Step-by-Step Buying Process (with Tips for Non-Japanese Speakers)

Buying a house in Japan involves several stages, but with the right preparation it can be straightforward. Here’s a step-by-step guide to the process:

- Determine Your Budget and Financing:

Start by crunching the numbers. Consider not just the property price but also additional costs (taxes, agent fees, insurance, and potential renovation costs for older homes). If you’re paying cash, know your absolute budget ceiling. If you need a loan, begin discussions early. Foreign residents in Japan should check with banks like Shinsei or SMBC for home loan options; non-residents might explore financing from abroad or plan to purchase in cash. Also, factor in currency exchange rates if your money is in another currency – as rates fluctuate, so does your effective cost in yen. Tip: It’s wise to have extra funds set aside (around 5–10% of the property price) for closing costs and initial repairs. - House Hunting and Finding an Agent:

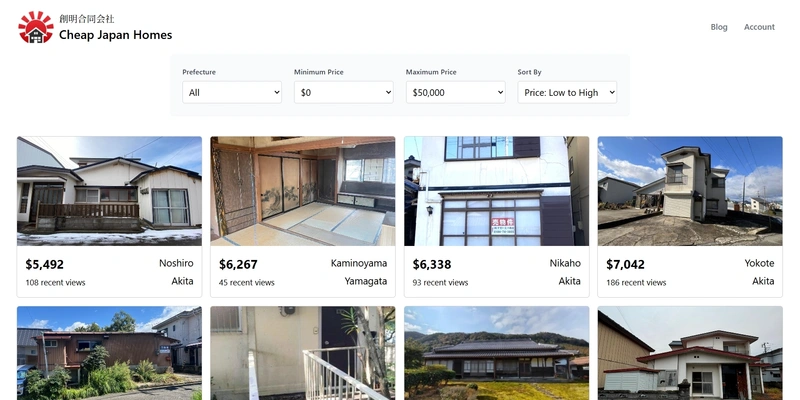

With budget in hand, start searching for properties. Here’s how Cheap Japan Homes makes it easy to filter by price range, like under $50,000:

In Japan, most real estate listings are handled by agencies and appear on multiple listing sites. If you read Japanese, sites like SUUMO, Homes, or AtHome have the most listings. For English speakers, look at portals like RealEstate.co.jp or specialized sites focusing on cheap houses in Japan (we’ll list some in the next section). It’s highly recommended to engage a bilingual real estate agent who has experience with foreign clients. They can guide you through listings, set up viewings, and explain terms. In many rural areas, English-speaking agents might be rare, but don’t let that deter you – some urban agents will work nationwide, or you can enlist a translator for critical meetings. Tip: If you’re browsing online from overseas, take advantage of virtual tours or video walkthroughs when available. This can help you narrow choices before an in-person visit.

- View Properties and Do Due Diligence:

Once you identify promising houses (for example, a few akiya in a region you like), schedule viewings. It’s best to visit in person if possible. Pictures might not reveal a moldy smell, structural issues, or neighborhood quirks. When viewing, check the condition of the roof, walls, plumbing, and electrical systems – old homes may need upgrades, and looks can be deceiving. This home looks great outside but needs major work on the interior:

- Making an Offer and Negotiation:

When you find “the one,” it’s time to make an offer. In Japan, properties often sell close to the asking price, especially if priced reasonably. You can certainly attempt a lower offer, but big low-balls might be ignored – modest negotiations (a few percent off, or asking for repairs to be done) are more common. Your agent will prepare an offer letter or application to purchase. If the seller accepts, you’ll typically need to pay a small earnest money deposit (手付金 tetsukekin) to secure the deal. This is usually around ¥100,000 to ¥500,000 (about $700–$3,500) to show good faith. This amount later counts toward the purchase price. At this stage, you may also need to show proof of funds or financing approval, especially if you’re not a resident. Tip: Be prepared to provide identification (passport) and if you have no residence card, an affidavit of ID (a notarized document) may be required by some agencies for foreigners to proceed with a contract. - Sign the Contract (Sales Agreement):

Next comes the formal contract signing, usually a few weeks after offer acceptance (though it can be sooner). Before signing, a licensed real estate agent is legally required to read and explain the Explanation of Important Matters (Jūyō Jikō Setsumeisho) to you. This document covers all details about the property: boundaries, any liens or rights, zoning, building restrictions, and known defects or needed repairs. If you aren’t fluent in Japanese, ensure you have a translation or an English version – many agents catering to foreigners will provide an English summary, but the official document will be in Japanese. After this, you’ll review and sign the Sales Contract (売買契約書), which states the price, payment schedule, and closing date. At contract signing, it’s common to pay the down payment, often 10–20% of the purchase price (minus any earnest money you already paid). You’ll also pay the agent’s commission at this point (typically 3% of the sale price + ¥60,000 + tax). Once the contract is signed by both parties, it’s legally binding. - Closing and Transfer of Ownership:

The closing is when you pay the remaining balance and the property title is transferred to your name. This usually occurs 1–2 months after the contract (negotiated in the contract). On closing day, you, the seller, and a judicial scrivener (司法書士) meet (often at the scrivener’s office or the bank). The judicial scrivener is a legal professional who handles the official registration of the property to the new owner’s name. They will have prepared the paperwork to update the land registry. You (the buyer) will transfer the remaining funds – typically via bank transfer or a cashier’s check – to the seller on that day. Once payment is confirmed, the scrivener submits the change of ownership to the government. You’ll receive the keys and a copy of the new property registration showing you as the owner. Congratulations – you now own a house in Japan! Tip: If you’re overseas and cannot attend in person, you can give power of attorney to the scrivener or a representative to handle closing for you. However, Japanese banks often require the buyer in person for the money transfer if done domestically, so plan ahead. - Post-Purchase Tasks:

After closing, there are a few more things to handle. First, if you haven’t already, set up accounts for utilities (electricity, water, gas, internet) in your name. This might involve calling local utility offices – your agent can assist or the seller might help with the transition. Next, ensure the local city office knows about the change of ownership for property tax records. (The judicial scrivener usually notifies them, but verify that you as the new owner are on record to receive the annual tax bills.) If you’re not living in Japan, you’ll want to designate a tax agent locally to receive these bills. Also, consider home insurance – you can get fire and earthquake insurance for your new house. Earthquake insurance is optional but worth considering given Japan’s seismic activity. Finally, if the house will remain vacant for long stretches (for example, a holiday home), plan for its upkeep: arrange for someone to check on it, keep the grass cut, and air it out, as Japan’s climate can be tough on empty homes (mold and pests can appear in unused houses).

Tips for non-Japanese speakers: Throughout the process, having bilingual support is key. Work with a real estate agent who can speak your language or at least English. All official documents will be in Japanese, so get translations for anything you sign. Don’t hesitate to use translation apps for day-to-day communications, but legal terms should be professionally translated. Japan’s process is paperwork-heavy, so expect a lot of documents. If you aren’t in Japan, know that much of the process (from viewing to signing) can be handled remotely with the right representation, but a trip to Japan to house-hunt and close the deal is very beneficial. Many foreigners have successfully navigated this process – with preparation, you can too!

Where to Find Listings (Including CheapJapanHomes.com)

Finding the right property is half the battle. Fortunately, there are several resources to help you find listings – especially cheap houses and akiyas:

- Cheap Japan Homes (CheapJapanHomes.com): Cheap Japan Homes is a site dedicated to affordable properties in Japan, particularly aimed at foreign buyers. We list akiya and other cheap houses in Japan with information in English. One handy feature is the ability to search by price range – for example, you can view properties under $30,000 easily. Our site aggregates deals across Japan, so you don’t have to check dozens of separate akiya bank websites. It’s a great resource to quickly see what’s available at the lower end of the market, all in one place. Many listings include photos and descriptions in English, and new deals are added regularly. Since we’re writing this guide for 2025, be aware that inventory can change fast – if you see an appealing listing, act on it or inquire, because the best deals can get snapped up by enterprising buyers. Here are a few current listings featured on Cheap Japan Homes:

- Real Estate Portals (Japanese): Websites like Suumo and AtHome are the big property listing portals in Japan. These are in Japanese and list everything from city apartments to country houses. You can use browser translation to navigate them. They have filters for location, price, property type, etc. However, many listings on these sites may be focused on standard homes rather than ultra-cheap akiya. Still, you can sometimes find rural gems there if you search by area and price (e.g., set max price low).

- Akiya Banks: An Akiya Bank (空き家バンク) isn’t a financial bank – it’s a term for databases run by local governments listing vacant houses for sale (often very cheap, sometimes even free). Many rural prefectures and towns maintain their own akiya bank websites. For example, Nagano, Tochigi, and other regions have online listings of abandoned homes seeking buyers. Local authorities are literally giving away some houses or offering them for as little as a few hundred dollars in order to lure new residents. These sites are usually in Japanese and may require registration to see details. They also sometimes have conditions (priority for people willing to move in, etc.). Browsing akiya banks can be fascinating – you might find a farmhouse on a large plot for next to nothing. A drawback is that the interfaces are clunky and you’ll likely need translation help. Still, it’s the place to find the cheapest houses in Japan, often well under $30,000.

- Other Niche Websites: There are a few other sites and services that specialize in old or rural houses. OldHousesJapan.com lists traditional homes (often higher-end restorations or historic homes). Akiya & Inaka is another platform focusing on vacant homes for expats and has English support. Social media can also be a source – Facebook groups or Instagram accounts (like cheapjapanhomes on Instagram) sometimes showcase featured properties. For instance, there have been posts about “free houses in Japan” on Instagram which draw a lot of attention. Keep an eye on those channels if you want to catch a deal via word of mouth.

- Real Estate Agencies: Especially if you have a particular region in mind, contacting local real estate agencies can uncover listings not widely advertised. In rural areas, some homes for sale might just have a sign on the door or be known to the town office. A local agent can find these. If language is a barrier, look for agencies in nearby cities that have some English-speaking staff or use a translation/intermediary service.

Note: When browsing listings, if you’re not fluent in Japanese, use translation tools or work with someone who can translate. Akiya listings often come with notes about conditions of purchase (like “must start renovation within 1 year” or “buyer must reside in the town”). Make sure to have those details clarified.

Among these resources, Cheap Japan Homes (cheapjapanhomes.com) stands out for convenience and English-friendly interface. It’s definitely worth checking as you start your house hunt – they even highlight properties that are unbelievably cheap (some under $10,000 or “free” with conditions). In the next sections, we’ll discuss what costs to expect beyond the listing price and the pros and cons of buying these abandoned homes.

Hidden Costs and Renovation Considerations

Buying a house – especially an older or super cheap one – comes with costs beyond the sticker price. It’s crucial to budget for these hidden costs and renovation needs when buying property in Japan.

1. Purchase Taxes and Fees: When you buy real estate in Japan, there are a handful of one-time taxes and fees to pay at closing or soon after:

- Stamp Duty: A tax stamp affixed to the contract. For a typical cheap house (under ¥10 million or ~$70k), this might be around ¥10,000 or less (often even zero if under ¥5 million). Higher property prices incur higher stamp duties on a sliding scale.

- Property Acquisition Tax (不動産取得税): A one-time tax levied by the prefecture, usually 3–4% of the assessed property value. For residential homes, a reduced rate of 3% often applies (as of 2025 the reduction is in effect). If you buy a super cheap akiya, the assessed value might be very low, so this tax could be minimal – but don’t forget it.

- Registration and License Tax: Paid to register the change of ownership. Roughly 0.4% of the property’s value for land and 2% for the building’s book value (often buildings have low book value if old). The judicial scrivener will calculate and handle this.

- Judicial Scrivener Fee: For their services in registering the title – typically a few hundred dollars (maybe ¥50,000–¥100,000, depending on complexity).

- Realtor Commission: If an agent was involved, the buyer typically pays 3% of purchase price + ¥60,000 + 10% tax (that’s the legal maximum fee) to the agent at contract signing. On a ¥3,000,000 house (

$20k), that’s about ¥150,000 ($1k) fee. - Other Closing Costs: Minor fees like obtaining certificates, an affidavit translation if you’re overseas, etc., might add up to a small amount.

2. Ongoing Taxes: Every year, you must pay Fixed Asset Tax (固定資産税) and possibly City Planning Tax (都市計画税) to the local government. Fixed Asset Tax is 1.4% of the assessed value of the land and building combined. City Planning Tax (if the area is designated for city development) is an additional 0.3%. For a rural property, these taxes are often very low because land values are low. For example, if a property’s assessed value is ¥2,000,000, the annual fixed asset tax would be about ¥28,000 (~$190) (source). Not too bad, but it’s yearly, so include it in your budget. The assessed value is usually lower than market price, especially for old houses. These taxes are billed in spring each year. If you buy partway through the year, the seller and buyer usually prorate the tax payment at closing.

3. Renovation and Repairs: This is the big one for akiya purchases. Many cheap houses in Japan are cheap for a reason – they might need significant work. Common issues include leaky roofs, outdated electrical wiring, no proper heating (many old homes lack modern HVAC), termite damage in wooden beams, or even structural reinforcement needs. Japanese old houses often require insulation and retrofitting to meet current earthquake codes. All of this can be expensive. It’s not unheard of to spend tens of thousands of dollars renovating an akiya to make it comfortably livable. In some cases, the renovation could cost more than the purchase price itself. Always get an inspection or at least a contractor’s opinion on what it will take to fix a place up. If you’re handy and plan to DIY some renovations, note that the DIY scene in Japan is less extensive than in some countries – certain materials or tools might be harder to find, and you might be required to use licensed professionals for certain tasks (like electrical work).

4. Infrastructure and Utilities: Check what infrastructure the property has. Some rural homes might not be connected to city sewer lines (meaning they have a septic tank that might need replacement or frequent emptying). Water could be municipal or a private well. Internet service might be slow or unavailable without costly installation (fiber may not reach every village). If a house sat empty, the water pipes could be rusted or frozen, and the electrical panel might be outdated. Plan to spend on updating these essentials. Also, Japan’s winters can be cold – budget for installing heating (maybe a kerosene heater, wood stove, or heat pump) if none exists.

5. Demolition (worst case scenario): In some cases, an akiya is in such bad shape that it’s not worth renovating. You might want the land to build new, which means demolishing the existing structure. Demolition in Japan costs money (you usually pay contractors to tear down and haul away a house). Depending on the size, demolition can cost from ¥500,000 to several million yen. The upside is that local governments sometimes offer subsidies for demolishing unsafe old houses (since it improves the neighborhood). Also, note that vacant land is taxed higher than land with a house on it (to discourage leaving lots empty), ironically – so some people leave a dilapidated house standing to keep lower taxes. Factor this in if your plan is to rebuild.

6. Miscellaneous and Soft Costs: Don’t forget the small stuff: moving costs (if you’ll be bringing furniture), furniture/appliances (many akiya come empty or with junk that needs removal), connection fees for utilities, property insurance (optional but recommended, especially fire insurance). If you’re not residing full-time, maybe the cost of a local caretaker or periodic inspection. While these are not huge individually, together they add to the true cost of making the house habitable.

Renovation considerations: If you’re buying an akiya, have a clear plan for renovation. Are you hiring local contractors? If so, get multiple quotes. Rural contractors might be cheaper than city ones, but some areas have a shortage of tradespeople. The traditional carpentry skills for old kominka (farmhouses) are dying out, which can make authentic restorations pricey. Alternatively, if you’ll DIY, ensure you have the time and skills for it – it can be a “painstaking process” as one YouTuber’s akiya renovation journey shows.

On the plus side, the Japanese government and some prefectures offer renovation subsidies or tax breaks for people who take on akiya projects. These programs can help cover part of your costs (for example, some areas might give ¥1 million towards renovation if you move in). Be sure to ask the local city office about any incentives for vacant house buyers – as of 2025, many local governments are eager to assist anyone willing to revitalize a long-empty home.

In summary, do not underestimate the hidden costs. A house listed for $20,000 might ultimately cost $50,000 by the time it’s fully in shape and all fees are paid. It’s still a bargain compared to many countries, but go in with eyes open. As one expert noted, there’s a lot of hype about these cheap houses, but “it’s a huge commitment” to restore them properly. With careful due diligence and budgeting, you can avoid unpleasant surprises and successfully turn an abandoned property into a lovely home.

Pros and Cons of Akiyas (Abandoned Homes in Japan)

Buying an akiya – an abandoned or vacant home – in Japan has become popular, but it’s not for everyone. Let’s break down the key pros and cons of akiyas for a foreign buyer:

Pros of Buying an Akiya

- Ultra-Low Purchase Price: The biggest draw is obviously cost. Akiyas can be incredibly affordable – sometimes even free. There are cases of local governments listing homes for $500 or literally $0 (with certain conditions). More commonly, you’ll find rural houses for a few thousand dollars or tens of thousands. For example, an Australian YouTuber bought a large 30-year-old farmhouse in Ibaraki for only $23,000. These low prices mean entry into the Japan real estate market with minimal investment. You might be able to buy with cash what would normally require a big mortgage elsewhere.

- Land and Space: Many akiyas include the land and are standalone houses (not condos), often with gardens or yards. You could get a spacious traditional house with multiple rooms, storage sheds, and a sizeable plot. This is a stark contrast to expensive tiny apartments in the cities. If you’ve dreamed of a big house in the countryside – garden, fruit trees, maybe a mountain view – akiyas make it possible on a small budget. In some listings, the land itself would be worth more than the asking price if it were in a more populated area.

- Authentic Japanese Living Experience: A lot of akiyas are old kominka (folk houses) with traditional architecture – think wooden beams, clay tile roofs, tatami rooms. Owning one gives you a chance to preserve and live in a piece of Japanese heritage. It’s appealing for those who appreciate Japanese aesthetics and want an authentic lifestyle. Some buyers turn these houses into vacation homes for themselves, or into holiday rentals for tourists seeking a countryside experience. There is growing interest in staying at traditional homes, so it could double as a unique Airbnb-style rental when you’re not using it.

- Less Competition: In popular urban markets, you’d compete with many buyers. But in the akiya market, especially deep countryside, you might be the only interested party. This means you can negotiate calmly or take your time deciding (with some exceptions if a property goes viral online). Also, as a foreigner, you might be tapping into a market segment that many domestic buyers shy away from (some Japanese avoid old homes due to cultural preferences for new construction). That can be an advantage for you.

- Community Incentives: As mentioned, many local governments roll out the red carpet for people willing to move in. This can mean subsidies, grants, or tax breaks for renovation. Some towns might offer a cash incentive for each child you bring into the school system, or free consulting with architects, etc. Beyond financial incentives, you might find a warm welcome from a community eager to have new residents (you could become somewhat of a minor celebrity in a small town as “the foreign family that restored the old house”). If you’re looking to integrate and make local friends, this can be a great way.

- Potential Investment Upside: While one shouldn’t buy an akiya purely to make money (resale values are uncertain), there is potential if you choose wisely. A property in a scenic area could be turned into a guesthouse or B&B. Or if Japan’s rural revitalization efforts succeed over time, values might rise. Even if not, your cost basis is low, so the risk is limited. Some foreign buyers see akiya as a fun project or part-time hobby that could at least pay for itself eventually via rental income or farm produce (if you use the land).

Cons of Buying an Akiya

- Renovation and Repair Costs: The flip side of the low price is often high renovation cost. As discussed earlier, many akiyas are in poor condition. Restoring a neglected property can be an enormous task. Roofing, plumbing, electrical, structural fixes – it all adds up. If you’re not prepared, you could end up with a money pit. One expert warns that while giant farmhouses seem like a bargain, “it’s a huge commitment and there aren’t many contractors that can fix them up”. Essentially, you might save on purchase price but then spend double or triple on making it livable. Always consider total renovation needs when evaluating an akiya.

- Maintenance and Upkeep: Even after renovation, an older home requires more upkeep. These houses weren’t built with modern low-maintenance materials. You may need to regularly treat for insects, maintain the wooden structures, repair leaks, etc. If the house will sit vacant part of the year, maintenance is even tougher (unused homes deteriorate faster). Budget time and money each year for maintenance tasks. If you live far away, you might need to hire someone to check on the property periodically.

- Location and Convenience: Akiyas are typically in rural areas or small towns. That means you could be far from conveniences like supermarkets, hospitals, and train stations. Public transport might be limited, so having a car is often a necessity in the countryside (which adds the cost of buying and maintaining a car in Japan). Also consider social factors: rural depopulated areas may have very few young people, schools might be closing, and healthcare access might be limited. It can be a wonderful quiet life, but it’s a big change from city living. Some people feel isolated after the initial novelty wears off.

- Resale Value and Liquidity: Japanese houses (except in prime city locations) generally depreciate in value over time due to the way the market prefers new construction. An akiya you buy for cheap might have very little resale demand. You should buy because you want to use and enjoy the house, not to flip it. It could take a long time to find a buyer if you needed to sell. In the worst case, it might become a burden if you can’t sell it easily (some Japanese owners literally abandon houses because they can’t sell and don’t want to pay taxes – contributing to the akiya problem). So think of it as a lifestyle purchase, not a financial investment (with a few exceptions where location is very good).

- Utilities and Amenities Gaps: As mentioned, some akiyas lack modern amenities. You might have to live with or upgrade things like squat toilets, no central heating, or a single 100V electrical circuit for the whole house. Internet might be slow. If these are crucial to you, factor the cost to modernize. Not every rural area has fiber-optic internet, for example – some remote homes might only get satellite internet. Water quality from wells can vary. These are solvable issues but are part of the reality of countryside properties.

- Language and Bureaucracy: If you’re not fluent in Japanese, managing a renovation or dealing with local town officials (for permits, etc.) can be challenging. Buying the house is just step one – what follows could be a lot of paperwork (building permits, residency registration in the town, etc.). In rural areas, officials may not speak English at all. Likewise, contractors likely won’t. You might need a translator or a bilingual project manager if doing major work. This can add complexity and cost. There’s also the cultural aspect of being a newcomer in a traditional community – it’s important to be respectful of local customs and neighbor relations (which might include joining area gatherings or duties).

- Potential Conditions or Strings Attached: Sometimes, those ultra-cheap deals come with fine print. For example, a town giving a house for free might require that the new owner actually move in and reside there as a primary residence, or that you commit to farming the attached land. Failing to do so could void the deal. Not all listings have conditions, but some do (especially if it’s through a government program). Always check if there are any residency or usage requirements. If you just want a vacation home, ensure it’s okay to use it as such. Also, if the house is historically significant, there may be restrictions on altering it.

In summary, buying an akiya can be amazingly rewarding – you get a cheap house, a new adventure, and the chance to immerse yourself in Japan’s countryside. But it comes with significant challenges that you need to be prepared for. It’s a bit of a “buy a lifestyle, not just a house” scenario. For those up to it, it can be great. For others, a more modern home at a higher price might be a better fit.

Personal Stories and Examples

To illustrate the journey, let’s look at a few personal stories of foreigners buying property in Japan:

- Australian Couple’s Retirement Akiya: In 2023, Deborah and Jason Brawn from Australia purchased an abandoned house (akiya) in rural Japan for about $23,000 (3.5 million yen). Their akiya, a 7-room traditional home built in 1868, had been sitting empty. They decided to restore it as part of their retirement plan. Over the next few years, they plan to renovate the house while splitting time between Japan and Australia. One crucial lesson they share is the importance of integrating into the local community. They believe being accepted by neighbors and participating in community life is key to long-term happiness in the Japanese countryside. This story shows that with a modest sum, a foreign couple could secure a piece of Japanese history and actively work on making it their dream home for retirement.

- The Tokyo Llama Project (DIY Farmhouse Renovation): An Australian known by the handle Tokyo Llama took on a massive DIY project, which he documented on YouTube. He bought a 1400 m² farmhouse in Ibaraki prefecture (about an hour from Tokyo) for only $23,000. The house was relatively young by akiya standards (around 30 years old) but needed a lot of work. Over many videos, he shows the painstaking process of tearing down walls, replacing floors, and upgrading the century-old kominka to modern comfort. His journey attracted viewers worldwide, proving that with determination (and carpentry skills), a foreigner can turn a cheap countryside house into a beautiful home. It wasn’t easy – he had to handle Japanese hardware stores, local contractors for certain tasks, and the sheer labor of renovation – but it’s an inspiring example for DIY enthusiasts.

- Swedish Buyer in Suburban Tokyo: Akiyas aren’t only in remote villages. In one case, a Swedish man purchased an 86-year-old house in Setagaya Ward, Tokyo – a rather upscale area – for about $69,000. How was it so cheap? It was a fixer-upper “as-is” sale, likely because the house was old and small by Tokyo standards, and the seller just wanted land value. The Swede found this deal via an expat-focused service (Akiya & Inaka). He then invested in renovating the home. This example is interesting because it shows even in big cities like Tokyo, there are opportunities to buy an old house at a fraction of the usual market price – if you’re willing to renovate. It’s not always all countryside; sometimes urban akiya exist (though rarer and often snatched quickly). For this buyer, it meant owning a freehold house with land in Tokyo, which is extraordinary given Tokyo’s typical real estate prices.

- Hypothetical Example – The Remote Worker’s Retreat: Imagine an American IT professional who can work remotely and has fallen in love with Japanese culture. He finds a ¥5,000,000 (about $35,000) akiya in a mountain town in Nagano – a quaint cottage with a gorgeous view, but it needs some updates. He buys it, spends another $30k renovating it into a cozy home with modern amenities, and splits his time working from his Japanese retreat and traveling. He becomes part of the local community, enjoys weekend hikes and hot springs, and even opens part of the house as a guesthouse for tourists during ski season. This hypothetical story is increasingly plausible in the post-2020 world of remote work. Japan’s countryside can offer a peaceful, fulfilling lifestyle for those who can work from anywhere, and the low cost of entry for housing makes it enticing.

Each story (real or imagined) highlights different aspects: super low cost but lots of elbow grease (Tokyo Llama), strategic city purchase (the Swede in Tokyo), lifestyle and community (the Brawns), or leveraging remote work to live abroad. The common thread is that foreigners can and do buy houses in Japan, from traditional farmhouses to suburban homes. With planning and perseverance, they turn those properties into livable homes and even thriving businesses.

If you’re considering following in their footsteps, take inspiration but also note the lessons: expect renovation challenges, engage with locals, and don’t rush the search for the right property. Now, let’s answer some frequently asked questions you might have.

FAQs

- Can foreigners buy property in Japan? – Yes. Foreigners can buy land and houses in Japan with no restrictions, even if you have no residency in Japan. You enjoy the same ownership rights as a Japanese citizen. Many non-Japanese have successfully purchased homes in Japan.

- Do I need a visa or residency to purchase a house? – No, you do not need to live in Japan or have a specific visa to buy property. Even a tourist can buy real estate. However, owning a house doesn’t grant you a visa or permission to reside beyond normal limits. If you plan to live in your home long-term, you’ll need to arrange a proper visa (work, spouse, investor, etc.) independently of the purchase.

- Will buying a house get me permanent residency or a “Investor Visa”? – By itself, no. Japan currently has no direct immigration program for real estate investment (unlike some countries that offer “golden visas”). You’ll have to qualify for residency through other means. That said, if you establish a business (say, a guesthouse or farm) you might explore a business manager visa, but simply owning a house is not a path to residency.

- Are there extra taxes or costs for foreign buyers? – Not extra for being foreign. You pay the same purchase tax, stamp duty, etc., as locals. No foreign buyer penalty taxes. The costs to watch out for are general purchase fees (around 5–8% of property price in total) and annual property taxes (~1.4% of value). If you don’t live in Japan, you may need a tax agent (basically a contact in Japan) for property tax purposes.

- How can I find cheap houses (akiyas) for sale? – Aside from engaging an agent, check out akiya bank listings for the specific town or prefecture you’re interested in, and browse sites like CheapJapanHomes.com for curated listings of cheap houses in Japan. Also keep an eye on RealEstate.co.jp and forums where people discuss akiya finds. Networking with local communities can help too – sometimes word of mouth will alert you to a house that’s about to come up for sale.

- What’s the catch with “free” houses in Japan? – You might have seen headlines about Japan giving away homes. It’s true some towns offer homes for extremely low cost or free, but usually with conditions. Often, you must be a younger family or agree to actually move in and renovate. The “free” house might also come with required expenses (like paying outstanding property tax or demolition of an unsafe part of the structure). Basically, nothing is truly free – you either invest money in fixing it or invest your commitment to the community (or both). Still, these programs are real and worth exploring if you’re open to relocation and community involvement.

- Can I get a mortgage as a foreigner to buy a house? – If you are a resident in Japan with a stable income, it’s possible. Many foreign residents have gotten home loans, especially permanent residents or those married to Japanese nationals, but it often requires more paperwork. Non-resident foreigners (living abroad) will find it very difficult to get a Japanese bank to lend for an akiya purchase. In that case, your options are to finance in your home country (like a personal loan or remortgaging a property you own elsewhere) or work with certain international lenders. There are a few Japanese banks known to work with foreigners (SMBC Trust, Shinsei, Prestia) but usually they cater to people residing in Japan. A small loan might not be worth the bank’s effort either. So, many akiya buyers pay cash. The good news is the amounts are relatively small; some even put it on a credit card or savings instead of a mortgage.

- What should I prioritize when renovating an old Japanese house? – Structure and weatherproofing first. Ensure the roof is sound and no leaks – Japan’s rain (and snow in some areas) can be severe. Then address any structural reinforcement (consult an architect if needed to see if additional supports are required for earthquakes). Update electrical and plumbing for safety (old wiring can be a fire hazard). Insulate if you plan to live there in winter (many old houses are drafty and cold). After that, you can tackle interior decor and layout changes. Always check if you need permits for certain renovations – generally interior work is fine, but if you alter the structure or expand, you may need approval. Hiring a local builder who knows code requirements is helpful. Also be mindful of preserving any historical character of the home; reuse materials from the house if you can (for instance, refurbishing old wooden sliding doors) – this can save money and maintain the charm.

- What is an akiya bank and how do I use it? – An akiya bank is typically a website or program run by a municipality listing vacant homes in that area. To use it, you often register (sometimes they ask for your basic info and intent). Then you can browse listings, which usually have photos, price (sometimes negotiable or listed as “consultation required”), and conditions. If you find one you like, you contact the municipality or assigned real estate agent for that property to express interest. They may help arrange a viewing. Keep in mind, many akiya bank listings are in Japanese and staff might not speak English, so you may need translation help. Some regions now partner with companies or NPOs that assist foreigners with akiya bank transactions. It’s a more involved process than a regular market sale, but it can yield special local deals.

- Are akiya only in remote villages? – Akiya are most common in rural areas, yes, but they also exist in suburbs of cities and even within cities (as the Setagaya example shows). 13.8% of all homes in Japan are vacant as of 2023, so the phenomenon is widespread. In big cities, an akiya is less likely to be a stand-alone house; it could be an old apartment or a tiny old house among new ones. Those tend not to be “free” but might still be cheaper than average for the location because of condition. The closer to a major city, generally the higher the baseline price. So if your goal is a truly cheap house, you’ll be looking at the countryside or smaller regional cities.

- What are the ongoing responsibilities of owning a home in Japan as a foreigner? – Mainly paying annual taxes, keeping the property from becoming a nuisance, and abiding by local regulations (e.g., garbage disposal rules, community association if any). If you’re not living there, you should periodically check the home or have someone do it – if a house is left completely neglected, the city can issue warnings or fines (in extreme cases of dangerous neglect). You don’t have to worry about any owner’s association unless it’s a condo or part of a housing area that has one. Also, if you decided to rent it out (even occasionally as a vacation rental), you’d need to follow the proper procedures (Japan has minpaku laws for short-term rentals). But if it’s just for personal use, it’s straightforward. Owning land means you’re also responsible for things like not letting weeds overgrow (potentially bothering neighbors) and respecting property boundaries.

These FAQs cover the common points most prospective buyers ask. If you have other questions, it’s wise to consult with a real estate professional or legal advisor familiar with Japan’s property market. Next, we’ll wrap up with some final thoughts and how you can start your own search for a home in Japan.

Conclusion: Ready to Find Your Japanese Home?

Buying a house in Japan as a foreigner may seem daunting, but as we’ve seen, it’s quite feasible and can be extremely rewarding. From understanding the legal freedom you have as a buyer to navigating the unique challenges of akiyas, you’re now equipped with a step-by-step guide and key insights. Whether you’re drawn by the charm of a countryside abandoned home in Japan or looking for an affordable dwelling for your Japan adventures, opportunity awaits in 2025.

If you’re inspired to take the next step, why not browse some real listings to see what’s out there? Head over to Cheap Japan Homes and explore their curated selection of budget-friendly Japanese properties. You can filter by region, price (try looking at the under $30,000 section to be amazed), and property type. Who knows – your future Japanese home might already be listed there, waiting for you to discover it.

Dive into the listings on Cheap Japan Homes and other resources mentioned. Imagine yourself owning one of those properties, and if the dream excites you, reach out for more information. Japan’s doors are open to foreign homebuyers, and with so many cheap houses in Japan on the market, there’s never been a better time to turn that dream into reality. Happy house hunting, or as they say in Japan, 頑張って (ganbatte) – good luck and go for it!